| Decades before Condoleezza

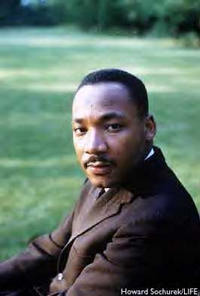

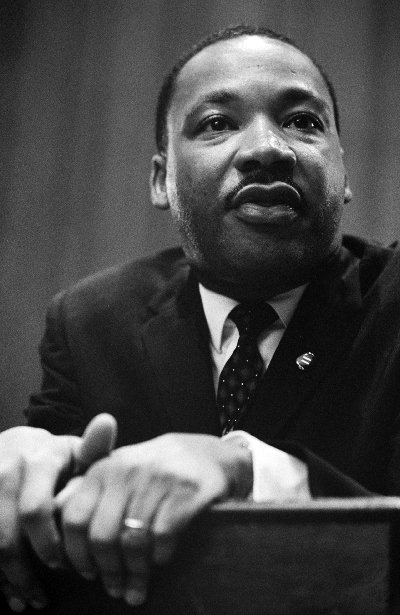

How a daring Martin Luther King speech in 1967 opened the door for black statesmanship

He called it a speech to break the silence. And it created an uproar. On April 4, 1967, addressing 3,000 people at New York's Riverside Church, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. denounced the Vietnam War as an "enemy of the poor" and called the U.S. government the "greatest purveyor of violence in the world." King's popularity waned until his assassination exactly one year later. But his speech had a lasting impact. Scholars and peace activists call King's words as relevant to today's war in Iraq as they were nearly four decades ago. What's more, in protesting the Vietnam War, King became the most prominent black American to criticize U.S. policies beyond civil rights. He forced the world to view his legacy beyond the Montgomery bus boycott and the "I Have a Dream" sound bite, while setting a precedent for black Americans to be recognized as more than advocates for racial justice. "The whole notion of black Americans having a major say on foreign policy is just something that would not have been conceivable," says Clayborne Carson, a history professor and director of the Martin Luther King Jr. Papers Project at Stanford University. "Diplomacy was something that was done by elitist white guys from Yale." Last Monday, on the holiday observing his birthday — he would have been 76 — peace protestors, scholars and civil-rights activists urged Americans to embrace the complexities of King — remembering not only the advocate for the poor but also the foreign policy critic. "When I go to other countries, it's very clear that he was more than a black civil-rights leader," says Carson. "But in the U.S., he's been perceived as just a black leader." It may seem a curious notion today, with African-Americans Colin Powell and Condoleezza Rice — the outgoing and incoming secretaries of state, respectively — helping to set American foreign policy. But at the time, King felt conflicted.

His decision came only after prodding by his wife, Coretta Scott King, and others in the movement. "In King's autobiography, he criticizes himself for taking a stand," says Carson. "Here was this person who had consistently denounced war but couldn't really speak out against this war." However, King decided to voice his opposition after Lyndon Johnson diverted money from anti-poverty programs to the war. King saw hypocrisy. He said the war hurt poor people and pointed to the irony of race relations. Blacks and whites could fight beside each other in another corner of the world "for a nation that has been unable to seat them together in the same schools," Carson says. He notes that while King's statements caused the civil-rights movement some harm — alienating the White House and some financial supporters of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference — they didn't ruin him. And when King finally spoke out, he did so with some relief, after years of being frustrated by his own indecision. "After that," Carson says, "he makes some of the most beautiful statements in the need of standing up for your conscience. He showed that taking a stand was extremely important." This year, peace groups used Martin Luther King Day to draw attention to the war in Iraq. "We feel like if he were alive today, he would be championing peace and would be very vehemently against this invasion in Iraq," says Holly Stadtler, an organizer of Finding Our Voices Coalition.

For King, non-violence was the means to social change on three fronts: militarism, racism and poverty. "They are all connected," says the Rev. Graylan Hagler, a civil-rights activist who counts King as an inspiration. "The `dream' is what the powers in this country feel that it is convenient to applaud. But it doesn't get to the place of critical analysis. "There are other speeches that end up being a critique of America, and they are relevant because the same system exists right now." Hagler, who once ran for mayor of Boston, has devoted his life to peace and protest, from Vietnam to South African apartheid. King's anti-war stand had a profound effect on him, but Hagler acknowledges its complexities. "It took King a while to get there," he says. "How could you speak about non-violence at home when we are inflicting all this violence around the world? "He began to see that what we do abroad is intricately linked to the status of our soul as a nation." In fact, it took King years to speak out publicly against Vietnam, even though he was opposed to the war for a long time.

In 1965, he first urged a ceasefire in Vietnam, but it would take two more years for him to make his first declaration of opposing the war during the speech at Riverside Church. King knew he risked alienating supporters and losing the focus of his civil-rights goals. "It was less clear what he would gain," says Carson, adding it wasn't just the civil-rights agenda that was in jeopardy. Speaking out on any other topic came with severe consequences for African-Americans in those days. Notes Carson: "When Paul Robeson and W.E.B. DuBois took a stand against the Cold War, it ruined their careers. "For a black person to enter into a foreign policy issue, it could end your career or maybe put you in prison. "King crossed a major threshold that most blacks couldn't." |

|