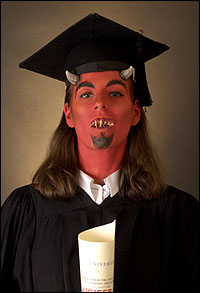

With corporate crime hitting the headlines daily, it's time to ask if our business leaders are being taught how to be soulless?

|

SAN GREWAL

In the past few weeks, about 150 applicants to some of America's most prestigious business schools embarrassed themselves and the programs they applied to. The applicants hacked into the admissions files at Harvard, Duke, Stanford, MIT and other universities, to try to find out ahead of time if they had been accepted. Instead, they got caught. MIT and Harvard responded by denying admission to all who broke the rules. The other universities are weighing their options. It's the latest in a growing list of events that have seen business schools live up to their reputation as factories producing greedy, unethical weasels. The fiascos at Enron, WorldCom, Tyco International and other companies that adopted the frat house model of corporate governance created the first wave of MBA bashing. The Apprentice, with its regular cast of hyper-ambitious business school kids who can't play together, brought the stereotype of MBA grads into people's living rooms. And now, the latest academic criticism of business schools and the students they produce has come down. Following last year's Manager's not MBAs, a condemnation of business school practices by McGill University business professor Henry Mintzberg, another indictment of business schools has been published. This time, it's in a top management journal, Academy of Management Learning & Education. The article, which was discussed in the Feb. 17 issue of The Economist, was authored by Sumantra Ghoshal, a respected management theorist from the London Business School. Ghoshal passed away last year, but not before writing what amounts to an apology for the way MBA programs have created poorly equipped, often unethical managers and executives who dominate the corporate world, creating a calculating business culture that affects everyone in it, MBA or not. |

`What happened with all the corporate scandals was like a nuclear disaster.'

|

|

His main criticism is that MBA programs operate as self-fulfilling prophecies. They use a strictly economic understanding of human behaviour — that we're all self-interested and self-serving — to rationalize why companies have only one purpose, to increase the value of their shareholders' stocks.

So, according to the criticism, students learn that unethical behaviour is excused because profits are the only goal. And that's why many in a generation of grads have done more harm to the business world than good. "I think it's quite a provocative article. I agree with a lot of it," says Pat Bradshaw, an associate professor at York University's Schulich School of Business. But she says unlike the students she taught 20 years ago, who accepted bottom line economic models without question, her students today represent the new profile of business grads. "Today's students are more socially conscious, more sophisticated. They recognize the old models benefited shareholders and had been constructed to give advantages to certain groups of people." And regarding ethics, she says students are now critical about scandals such as the recent Boeing case, which saw CEO Harry Stonecipher dismissed after an affair with a junior executive. "We ask them to think critically — `Maybe I shouldn't be having an affair when I'm in a senior position that's espousing ethical behaviour.' We need to take new perspectives on gender issues, ethics and power politics. There's a whole change happening." It's a change MBA schools have been forced to make. Let's say you're a university president, and you hear that ScrewYou Inc. just went under — and the CEO who cooked the books is a proud alumnus. In the competitive world of universities, you've got to protect your rep. Glen Whyte of the University of Toronto says the fallout from recent scandals will actually help turn around the failing reputation of business schools. "What happened with all the corporate scandals was like a nuclear disaster," says Whyte, a professor of organizational behaviour at the Rotman School of Management. Whyte acknowledges the bad reputation MBA grads have. He explains the Rotman School has been doing its part to turn that around. "On the front end of the problem is admissions. There is a real effort to recruit people who are unlike the people you see on The Apprentice. They express cultural and social sensitivity. We screen them for leadership skills and things like integrity — they don't have sharp elbows." Whyte doesn't agree with many aspects of Ghoshal's basic premise — that MBA curricula led directly to unethical managers and executives — but admits that business schools have drastically changed what they teach students, compared to two decades ago. With its strict adherence to the philosophy of economist Milton Friedman, who believes the only responsibility of corporations in a free society is to make as much money as possible for shareholders, the MBA degree became wildly popular with students and corporate recruiters during the Gordon Gecko era of the 1980s. However, Whyte says in today's business climate, courses on ethics and the social impact of corporations, along with decreased emphasis on classic economic models, is the new approach at more progressive schools. Personal interviews, essays and screening for integrity and leadership skills are weighed just as heavily as GMAT scores and undergraduate grades when considering applicants, Whyte says. But the stereotype of the business school grad remains: the hyper-ambitious, self-interested climber. "I'm ambitious, I'm not going to lie," says Prakash David, a second-year student in the MBA program at the Richard Ivey School of Business at the University of Western Ontario. "I don't apologize for people being ambitious. Are MBA students ambitious? Yes, they're very ambitious. There's a personal and financial sacrifice that's been made to be in a top MBA program. But I don't think we're being taught just the profit motivation. Corporate social responsibility and ethics has been instilled in us throughout the curriculum." Asked what he would like to do in the future, the 33-year-old, who has been involved with his business school's project to build a house with Habitat For Humanity in London, says he would like to get into mergers and acquisitions in Asia. It's a field that has traditionally operated using cost-cutting measures (widespread layoffs, outsourcing and decreased benefits) to make merged or expanded companies more efficient and profitable. It often leads to large social costs. "We introduced a course (in 2004-2005) called `Individuals, Corporations and Society' that looks at the effects of the relationships between those three components," says Tima Bansal, an associate professor at Ivey . "We are trying to teach students about things like the ethics of marketing and advertising. It's taken some soul searching on our part at Ivey — how do we give our students these sorts of new perspectives? What are we doing when we close down a plant? Does it make sense to pay CEOs this much money?" But York's Bradshaw wonders if there's been too much emphasis placed on ethics recently. "When I say to my students, `How many of you want to be CEOs, work long hours on interesting projects and take advantage of the opportunities out there?' fewer and fewer want to go for it. They want a balanced life. We've certainly got our bottom line thinkers, in finance, but I'm seeing less of them." One case study Bansal's classes have looked at involves a pharmaceutical company and its research into a drug that could prevent river-blindness, a widespread problem in Africa. "It's viewed as a Third World disease, so the company can't make any profits from producing the drug. The students are asked what the company should do and in the past a lot of students said no, there is no economic gain. "This year, seven or eight students — out of 60 — said no and the rest said the company should produce the drug." Whyte also mentions an example students at Rotman are asked to consider, regarding bonuses offered to some of Nortel's senior management. "Tying departmental performance to bonuses, which leads to a fudging of the books — that comes out of old classical economic assumptions." And he says those assumptions need to be reconsidered. Ivey's Bansal agrees with Ghoshal's article, but says things are changing drastically. "We had this dominant economic paradigm (the profit motive) that permeated institutional structures — more is better, that's just the way our culture is. Even we as a business school fought against that. "But what we can do now is allow students to re-activate their own value systems. What we can do is get them to think more critically about what's out there. " I think the business schools are saying, `We don't like what's happened with all these scandals, let's change the education, at least.'" |

|